“Hey _____, Someone likes you!” reads the first line of a Friendsy invite email. It continues, “Someone from Swarthmore is interested in you and would like to see if you are interested as well!”

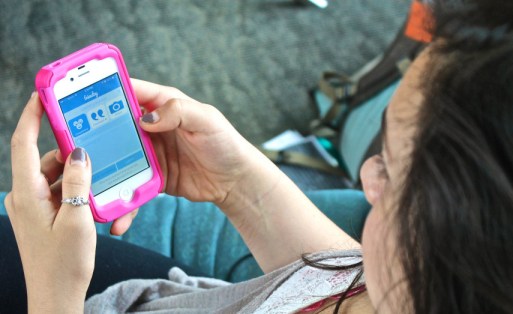

The invitation to join the new friend/dating/hookup social network, Friendsy, is almost as straightforward as the app prompts one to be with fellow classmates once they actually sign up. Each profile consists of a few pictures, major, social and/or athletic affiliation and class year, which ideally aid users in deciding whether they want to “friend,” “date” or “hook up” with the person displayed on the screen. The concept of being friends with, dating or hooking up with fellow classmates is not foreign to most college students, but declaring such desires in an online campus-exclusive setting (with the exception of Facebook circa 2004) isn’t so familiar.

Throughout Swarthmore’s history there have been traditions for everything from revealing senior crushes during the Green Bottle Party to meeting random Swatties through SwatDeck outings — and we’re not the only school with these practices.

We were also not the only school whose old traditions were joined by a new one in the tech-millennial milieu when Friendsy was released at approximately fifty colleges and universities around the country this past week.

In May of 2013, Princeton undergrads Mike Pinsky ’16 and Viadhy Murti ’15 launched a basic prototype of the Friendsy app at their own school and managed to register around one fourth of the campus. Throughout the year that followed, they worked on expanding and perfecting the app, which culminated this past summer at Princeton’s startup accelerator where they prepared for their big 50-school launch.

However, unlike many of the other schools with Friendsy, the Swarthmore Friendsy network does not just include Swarthmore, but the entire Tri-College Consortium.

Haverford student John* ’17 was happy about the inclusion of Swarthmore and Bryn Mawr on what he deemed “Tinder for the Tri-Co,” commenting, “I think that there should be more socialization between Bryn Mawr, Swarthmore and Haverford outside of just the classroom setting, and an app like this is a good starting place for the Tri-Co intermingling to happen.”

Whether Friendsy will truly encourage contact between students from the three schools remains to be seen, but, if nothing else, there is certainly more choice involved in this contact than in chance encounters between students at parties or during brief chats after class.

Friendsy-using Swarthmore student Harry* ’17 corroborated this feeling, describing the relative ease of looking at online profiles as opposed to the more effortful task of in-person pursuit, “You’re cherry-picking; you don’t have to go through the formalities of figuring out what other people want. I’m not always looking for a girlfriend or a hookup and I don’t have to pretend that I am.”

In this way, the app has some seriously positive implications for terminally Swakward students and our potentially pining friends-and-hookups-to-be in the Tri-Co. Because one’s identity is revealed to another person only after both people have pressed the same icon indicating “friendship,” “hookup” or “date,” there is safety for students who are too shy or uncomfortable with making such declarations in person.

As creators Pinsky and Murti put it, “Friendsy … aims to create more interactions between people and take relationships to the next level.” Simply put, Friendsy was made to facilitate and/or strengthen connections amongst students within their campus student bodies.

Pinsky and Murti advocated for the campus-exclusive format of the app for a small school like Swarthmore, saying, “Each school makes [Friendsy] its own thing, each school’s culture dictates what Friendsy looks like. People may already know each other so the risk of putting oneself out there is larger [without Friendsy].”

John agreed, commenting, “In real life, two people who could definitely ‘match’ with each other could end up walking by each other on the way to class everyday for four years and never even acknowledge that the other person exists.”

This brings up an interesting question. What’s more risky: anonymously voicing interest until you know that the interest is reciprocated, or never finding out that someone else was interested because you never had the gumption to express interest? The logic behind Friendsy seems to suggest the latter.

For some, however, the very act of establishing an internet presence on a friend/hookup/dating website is an announcement in and of itself — a “risk.”

Harry is unashamed to be on the website, sharing, “It’s not bad that someone can sense my presence on the internet. If it is something private, it shouldn’t be touching the internet in any way, shape or form … It’s sort of like if someone looks at me, they can guess that I’m thinking, but they don’t know what I’m thinking. People know I’m on the site, but they don’t know what I’m doing.”

Other students were more ambivalent about the assumptions that peers might make about their presence on Friendsy, regardless of the protection that certain features of Friendsy offers.

Several interviewees referred to the site as a “fuckbook,” and questioned whether people would actually use it “just for friends.” Some agreed that the friend button was a good default, but that overall, the friend button was “bullshit. I’ve got enough friends,” as Harry put it.

Raven Bennett ’17 was driven to the site because she was curious about how what she described as a “friend-oriented Tinder” might work. Bennett is aware, however, that other students do view Friendsy as Harry does — as place to lust after peers or find romance. And this fact makes her relationship to the site all the more complex.

“It’s kind of weird knowing that I have all of these alerts and that people want to hookup with and go on a date with me and I’ll never know who they are because I’m dating someone and I don’t feel like [finding that out] is appropriate. A tiny part of me is curious, but then I’m like ‘whatever,’” she said.

April* ’17 also currently has a boyfriend and shared Bennett’s sentiment, explaining, “I find out that someone wants to hook up with me but I can’t find out who they are and I can’t do anything with that information that ‘someone’ wants to hook up with me, so I’m just sitting here awkwardly.”

Still, if one goes about using the network exclusively for making friends, there are even more obstacles to overcome.

“I don’t know how looking at someone’s face and name and year is a good indicator of if I want to be friends with them … that led me to only click ‘friend’ for people I already know,” said Bennett.

John was both troubled and amused by the function of the app.

“Determining potential partners/friends based off of a few pictures and a small blurb is not very natural. Having said that, I have used Tinder in the past and use it here and there now, and find it absolutely entertaining,” he shared.

For platonic purposes, and potentially romantic purposes, too, then, Friendsy seems flawed.

Murti and Pinsky addressed to this concern, responding, “One of the cool things you can do on Friendsy is filter search based on elements of the profile, say if you want to know the department [someone’s in] or their year. We’re also working on building out the profile so that it is much more personalized … it’s something that’s in the works, and we’d love any sort of feedback related to that … we’re all ears.”

For students who are openly (or not so openly) using Friendsy for romantic pursuits, they consistently emphasize that their use of Friendsy is very “casual” and that the relationships they expect to come of using it will likely be casual, as well.

“No one wants to find their spouse on Friendsy … they just want to hang out with someone or hook up with someone,” explained April.

But for a service that is so protective of the identities of its members, a less casual motive is revealed.

Alternatively, perhaps, the safety of anonymity uncovers within users a simple desire to keep aspects of one’s life private. Many people question whether apps like Friendsy and Tinder make our social lives more or less private, cultivated, premeditated, erratic.

Negotiating which parts of life that we choose to keep private and public, especially on a campus so small, is no small task, and Friendsy has certainly complicated this mediation.

Again, Friendsy’s presence on campus is still too fresh to judge what its total impact will be, and it seems as though people haven’t quite warmed up to using it in its full capacity yet.

As John recalled, “I have talked to people who I already knew from classes, but have yet to actually use the app for what it was meant for, but I hope to soon once more people start to use it.”

And with 20,000 users currently, Friendsy is not slowing down. “Our goal is to hit 100,000 users,” said Pinsky and Murti. And as Friendsy grows, so too does its ability to shape our lives and our ability to decide how we shape it.

Harry shared some parting wisdom about being unwieldy with the power of Friendsy: “Don’t mess around with the buttons. Don’t click as a joke. You might not like what you find.” And in a community so small, and with an app still so unfamiliar to us, it seems as though we’d be wise to heed his advice.

*Names changed at the request of interviewees.

It’s touch my heart

Whould I get a random text saying I got liked from someone at some school and the text says invite lasts till midnight. But the the thing is I never used it. How did it get my number. Would I have to make an account before and I just forgot about it??